Chances are that you are calculating your Velocity the wrong way! The Velocity is the speed with which a team can deliver new, valuable, finished and tested features to stakeholders. This blog is about why the common way to handle estimates and planning does not give you that. And how applying a Lean view on the matter can show your real Velocity.

Background

Agile Estimation and Planning relies heavily on Velocity and Relative Estimates. They are all based on the concept of Story Points, a relative estimate of the effort it takes to implement the functionality of Story.

The Velocity is the rate with which a development team delivers working, tested, finished functionality to stakeholders. In the best of worlds this is the customer or user directly, however, in many cases there are still some separate testing activities carried out before this actually happens.

To calculate Velocity we cannot estimate in hours or days, because that would make Velocity a unitless factor (hours divided by hours). It is common estimate in Story Points, where User Stories are compared to each other and some known story as the prototype story to compare to. The idea is to decouple effort from time and instead base future commitments on empirical measurements of past effort executed per time/iteration.

The Stories are found in the prioritized list of Stories to be implemented (what Scrum calls the Product Backlog). The Product Owner should prioritize in which order the wanted features should be implemented.

Signs of Debt

Technical Debt is a term, alluding to the financial world, describing a situation where shortcuts have previously been made in development. In some future situation this will cost more effort, like bug fixes, rewrites or implementation of automated test cases. In situations where an existing organisation is transitioning to Agile there is usually a substantial Technical Debt that needs to be repaid. This is often signaled by

- the team struggles to find ways to handle trouble reports

- rewrites, often incorrectly labelled “refactorings”, are listed in the Product Backlog

The Trouble with Trouble Reports

Of course Trouble Reports need to be addressed as soon as possible. But in a legacy situation many Trouble Reports are found in the late stages of integration and verification, which can be months after that development was “finished”. The development team has moved on or even been replaced. So many of the Trouble Reports must first to be analysed before a correction can even be attempted. This makes them impossible to estimate. So putting them in the Product Backlog can only be done after the solution, and an estimate, is known.

A technique I recommend is to reserve a fixed amount of resources for this analysis. This limits the amount of work for Trouble Report analysis to a known amount. The method of reservation can vary from a number of named persons per week/day, a specific TR-day in the sprint or just the gut feeling of the team. The point is that the team now knows how much of their resources can go into working of the backlog. And adjustments can easily be made after a retrospective and based on empirical data.

This technique has a number of merits:

- known and maximized decrease in resources

- only estimatable items go in the backlog

- all developers get to see where Troble Reports come from

- team members are relieved from stress caused by split focus (“fix TR:s while really trying to get Stories done”)

Once a solution has been found the Trouble Report can be put in the backlog for estimation and sprint planning. (But the fix is often simple, once found, so a team might opt to not put the fix in the Product Backlog. Instead the fix itself can also be made as part of the reserved Trouble Report resource box. This avoids the extra administration and lead time.)

But, if the Trouble Reports are put on the Backlog and estimated as normal stories, we give Velocity points to non-value-adding work items!

Rewrites are Pointless

A system with high technical debt might need a rewrite of some parts. More often than not, these has been known for some time but always get low priority from project/product managers. And rightly so, they do not add any business value.

They still need to be done, though. The technical debt need to be repaid. So, what to do?

First I usually ask the developers if the suggested rewrite really is the smallest step to improving the situation? Often I find that if I push sufficiently hard, they can back down a bit and a smaller improvement presents themselves. This is good news since the smaller improvement is easier to get acceptance for. And once they are small enough, they can be kept below the radar of the PO.

If the rewrites are indeed put on the Backlog and estimated as normal stories, we give Velocity points to non-value-adding work items!

The Point of the Story

And this brings me to the core of this blog entry. Trouble reports and rewrites are things that need to be done, but a product owner should never need to see them. The team should be able to address these issues by themselves. They should be delivering working, tested, valuable software. The Product Owner should prioritize the new features.

This indicates that neither rewrites nor Trouble Reports should go into the Product Backlog.

How would a team know what to commit to then? Well, the (smaller) rewrites and the trouble reports (if put in the backlog) need to be estimated. We could do that the same way as previously. But there should be no points earned for these items.

What would this strategy mean then?

- The Product Backlog should not contain Trouble Reports or rewrite “stories”

- The Team should include a limited amount of necessary non-value-adding items in the iteration

- The Team needs to estimate non-value-adding items

- The Team commit to a number of points including non-value-adding items

- The Team Speed is calculated from all Done Done items

- The Velocity is calculated only from value-adding stories

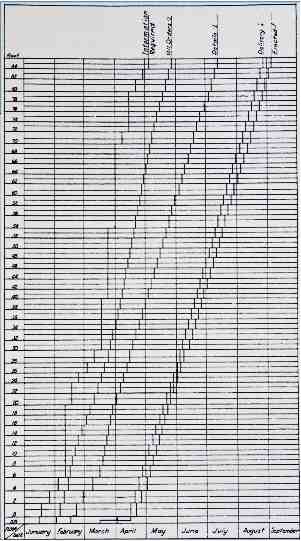

With this technique you will probably see an increase in Velocity as your Technical Debt is repaid. Something which I find very Lean.

The Real Velocity

The only Velocity that is really worth measuring is the speed at which a team can add business value. Then we need to make a difference between value adding work and extra work disguised as such.

I went to Budapest last week to do a workshop with the local management team of one of my customers. The goal was to talk to them about how they could move into the agile way of working. This was triggered by a move of some substantial product development from Sweden to Hungary. In Linköping, Sweden, I have been coaching a dozen teams in a transition to Agile, and I was asked to help the management to ensure that the transfer retain as much as possible of the Agile way of working that we have established.

I went to Budapest last week to do a workshop with the local management team of one of my customers. The goal was to talk to them about how they could move into the agile way of working. This was triggered by a move of some substantial product development from Sweden to Hungary. In Linköping, Sweden, I have been coaching a dozen teams in a transition to Agile, and I was asked to help the management to ensure that the transfer retain as much as possible of the Agile way of working that we have established.